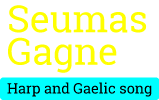

Title

Rooted in Celtic Music: A Seattle Harpist’s Discovery of a Musical Destiny

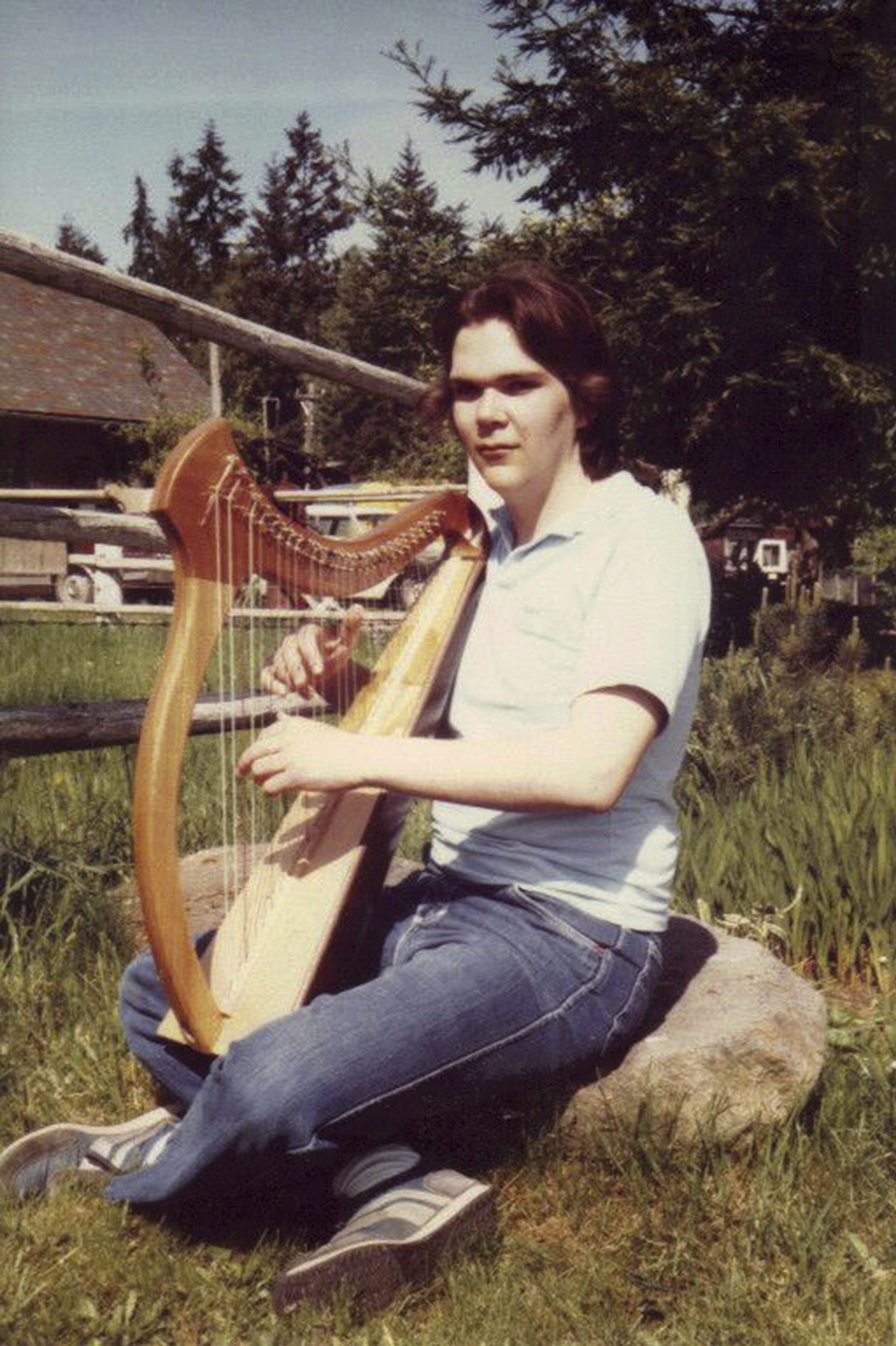

At 4 years old, Seumas Gagne knew he wanted to play the harp. Growing up in Poulsbo, Washington—nicknamed “Little Norway on the Fjord” for its nordic population and history—Seumas was exposed early on to Norwegian and Scandinavian arts and culture.

“I knew that I was destined to play the harp,” Seumas said. “Although I didn't find it a particularly exciting life at the time, I can now look back and see that growing up in Little Norway did give me a deep understanding of the value of traditional culture in the new world.”

Seumas’ mother grew up in Cleethorpes, England, and went into the Royal Air Force during World War II. His father emmigrated to Minneapolis from Sault Saint Marie, Ontario with his family when he was young, and was later drafted into the U.S. Air Force. It was during war times, in a bar in England, that the two met.

They were married in Colchester, England, and settled on Bainbridge Island in Washington, where they lived for 18 years. In 1968, when Seumas was still a toddler, they bought a 20-acre farm on the outskirts of Poulsbo, Washington. The family grew their own vegetables and fruit, and hay feed for the cattle they raised. They kept chickens and the occasional pig, and an artesian well high on a slope gravity fed water into the house. Seumas’ father had a workshop, and a forge where he made and repaired farm tools.

“I found the farm life to be quite tedious growing up,” Seumas said. “But looking back on it, I had an incredible education in what it really takes to live.”

A Musical Beginning

The only music Seumas heard growing up came from their living room. They didn’t have a stereo until Seumas was in middle school, and live music in Kitsap County was scarce. Seumas grew up with two brothers and a sister, all older, and they all took piano lessons growing up.

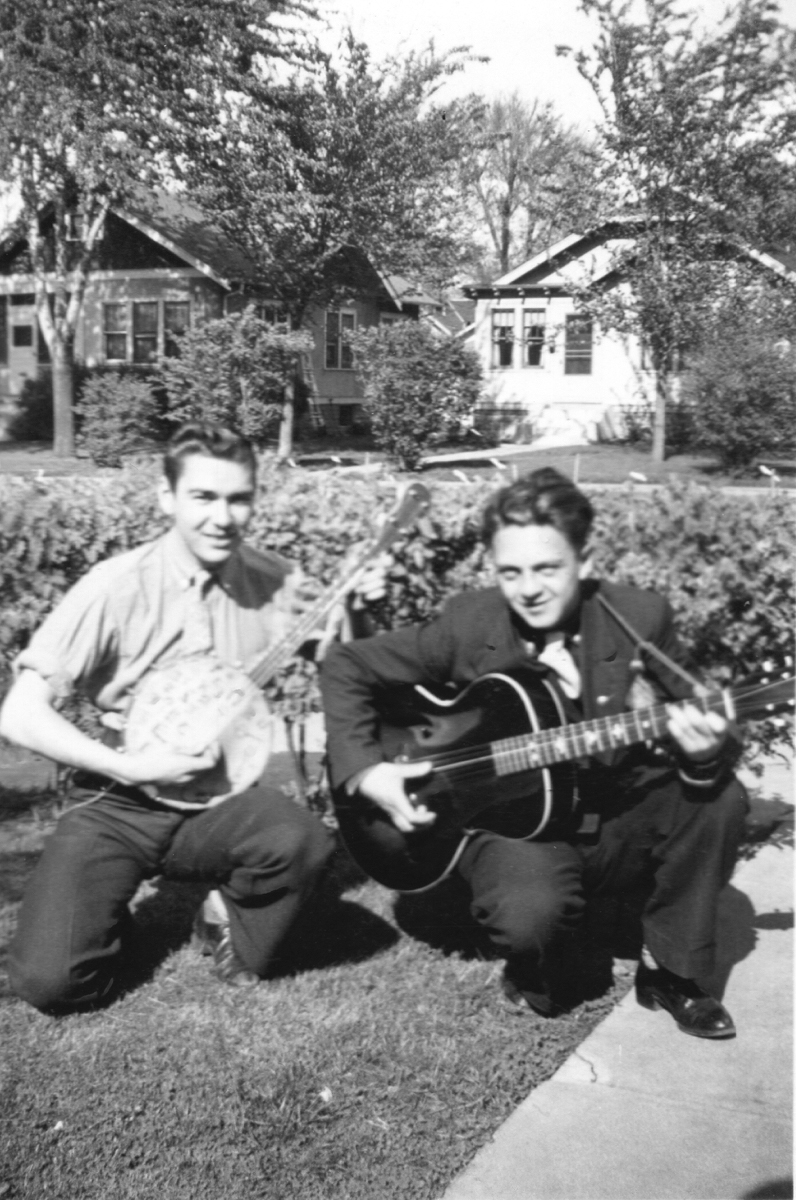

Seumas’ father played the violin earlier in his life, but gave it up during the Great Depression. When his father did get back into music, he moved on to Old Time music and taught himself the mandolin, banjo, guitar, and piano. Seumas fondly recalls hearing his father play the piano—particularly his favorite piece “Stardust” written by Hoagy Carmichael, and famously recorded by Nat King Cole, which his father would sing as he played.

“Although I have most definitely been inspired by many musicians along the way, that didn’t really start until I was already on the path myself,” Seumas said. “I was basically born knowing that I wanted to play the harp, and I’ve just followed that all my life.”

Destined to Play

For his fifth birthday, Seumas asked his parents for a harp. When he didn’t get one, he put aside thoughts of becoming a harpist and would not pick them back up again until years later. His interest in music, however, continued and he started his piano lessons at age 9.

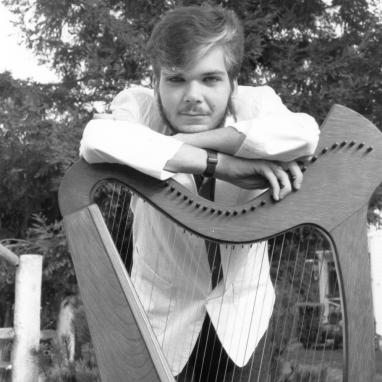

When he was 14, Seumas’ interest in the harp was renewed when his sister took him to the Puyallup Fair, where he saw Phillip and Pam Boulding playing the Irish harp and hammered dulcimer.

“I was completely transfixed the first moment I saw and heard the instrument that would define my life,” he said.

He found a harp teacher in nearby Suquamish shortly after the fair, and rented a small instrument. Six weeks after his first lesson, Seumas played his first gig at the opening of The Emerald Cottage restaurant on Bainbridge Island. He quickly built up a repertoire of generic British folk music, and in high school earned his pocket money playing at restaurants and weddings.

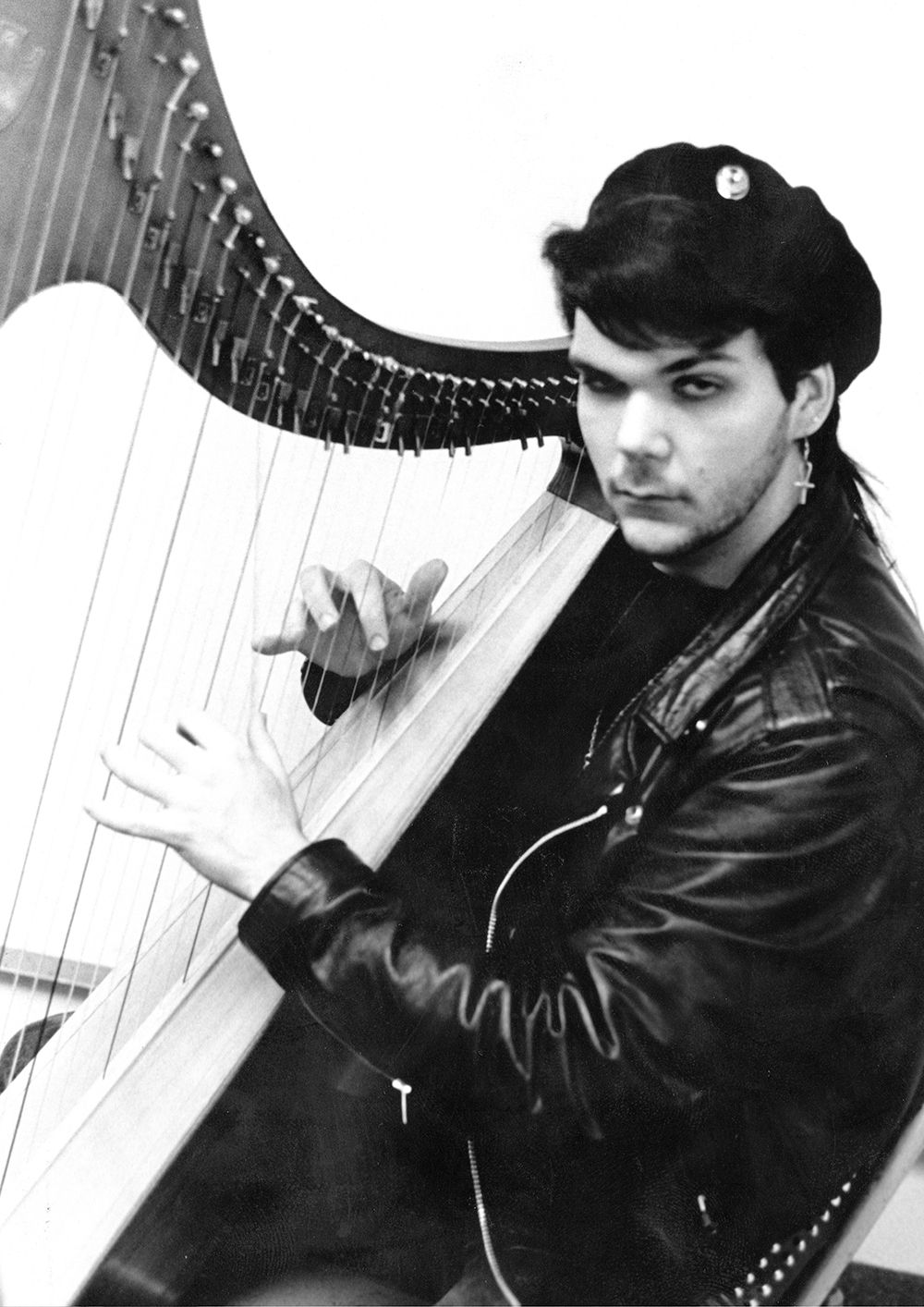

At the end of high school, he was faced with a difficult choice—to either get a job, or get a degree in a marketable area. After some encouragement from his friends and family, he decided to get a degree in music from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle—following in the footsteps of his older brother, who studied piano at Cornish. Seumas studied classical harp performance, with additional courses in composition and voice on the side.

“Life at Cornish was pretty great for me. I was surrounded by smart, creative, progressive people and I flourished,” Seumas said.

After graduating in 1989, Seumas considered a career as a classical harpist, but his heart wasn’t quite in it. He decided to go to work at the student lending agency where he’d been temping during his summer breaks.

Wicked Celts, and a Return to Gaelic Roots

After a lengthy break from music spent trying to fit in to the nonprofit corporate culture of the student lending world, Seumas was pulled back into the traditional music scene when his friend Síle Harris lent him her Jack Yule clàrsach harp for a couple years. Seumas searched for a Celtic band to join, but none were looking for a harpist. Not letting this hold him back, Seumas started his own band, Wicked Celts, in 1991.

The band made their first CD, “Prophecy and Blessing,” and managed to sell enough copies to cover their production expenses.

In 1995, Seumas’ father died, leaving Seumas his violin, which had been sitting in its case since the Depression. Seumas had the violin restored and tried some fiddling on the side, though he says he never quite mastered the instrument.

Around this time, Seumas decided to take a few lessons in Scottish Gaelic from an instructor, Richard Hill. Not looking to become fluent in the language, he at least wanted to be proficient at pronouncing the lyrics.

“My Gaelic class with Rich Hill didn't go as planned. Rich was charming, funny, a great singer, and a great teacher. Everything I learned made me want to get more; go deeper,” Seumas said.

Together the class members began organizing Gaelic weekends—bringing guest teachers from Vancouver, British Columbia for a large crowd of musicians and Scottish enthusiasts. In 1997, Seumas was part of a small group that wanted to make a bigger event happen—one that would draw big-name presenters and reach a broader audience. An event of this size brought with it liability and insurance concerns, and so the group decided to incorporate, taking the name Slighe nan Gaidheal (SLEE-uh nun GAY-ull).

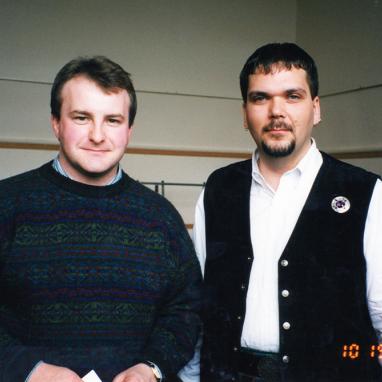

As a committee member for the first seven biennial educational festivals and co-chair for five of those, Seumas had the opportunity of meeting and learning from some of the most influential tradition bearers in the Scottish Gaelic world today. Over the years, he’s formed many friendships from these events—including Cathy-Ann MacPhee, Mary Macmaster, Wendy MacIsaac, Arthur Cormack, Gillebride MacMillan, Dr. Anne Lorne Gillies, and many others.

An International Success

In 1997, when his friends at the Vancouver Gaelic Choir were going to compete in the Royal Scottish National Mòd in Inverness, Scotland, Seumas and a few others decided to go along for the ride. He wound up competing in the senior clàrsach competition, and won the Elspeth Hyllestad Award for Solo Clàrsach performance. He performed in the competition winners’ concert that evening and was taken around the Mòd social events, where he put his language skills to practice as the only Gaelic-speaking American at the party.

When Wicked Celts disbanded in 2000 after changing lifestyles made regular collaboration a challenge, Seumas shifted his focus to Slighe nan Gaidheal, and to performing at festivals, highland games, and adjudicating competitions—traveling to interesting places and meeting spectacular people.

After Seumas performed at the Lone Peak Harp Festival, the festival organizer Bonnie Pulliam told him she wanted to keep booking him, but that it was harder to market a musician who didn’t have any recordings. This kicked off a multi-year effort as Seumas learned how to become a recording artist.

With the help of Michael Connolly of MTC studios, and Seumas’ Wicked Celts music collaborator, Christine Traxler, on fiddle/violin, Seumas released “Baile Ard” in February 2012. To celebrate the release of his first solo album, Seumas performed a concert at the Charlotte Martin Theatre at Seattle Center that he described as “a peak performance experience.” (View clips from the Baile Àrd Concert here).

One of the highlights of his album, Seumas said, was the title track “Oran do Bhaile Àrd,” which he wrote during the seven years he lived in the Ballard neighborhood. The song was featured prominently on BBC’s Scottish Gaelic radio station following the release.

“I’m very pleased with the reception it has received both here in my city and in Scotland,” he said. “The BBC’s Radio nan Gàidheal has been very generous in their praise.”

Redefining ‘Live’ Performance During a Pandemic

Though live performances have been put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic, Seumas has found new ways to share his music through virtual platforms. Starting on the Spring Equinox in 2020, he began recording short live performances on Facebook from his balcony with the Seattle sunset as his backdrop. Several nights a week, people tuned in to these performances and a lively community of regulars dubbed “The Balcony Folk” appeared in the likes and comments. After 112 episodes, Seumas brought season one of these performances to a close with a new march he composed to honor the balcony folk, calling it “The Solemn Beauty of the Night.”

With the easing of pandemic restrictions, Seumas continues to offer private instruction through online courses via Zoom as well as in person. He is preparing for his next album project, and looks forward to a time when he can get back into the recording studio.